The Modern 2020 International Conference on Monitoring in Geological Disposal of Radioactive Waste will be held from 9 to 11 April 2019 at Cité Universitaire, Paris, France.

http://www.modern2020.eu/final-conference/home.html

On Wednesday 10th April, Curator Ele Carpenter and artist Andy Weir will present a poster, a paper and particpate in a roundtable citizen stakeholder discussion on 'How to Reveal the Underground: through Data, over Time and in the Present?' Their extended abstract, authored along with Thomson & Craighead will be published in the conference proceedings, and below.

Nuclear Culture and Citizen Participation: Networked and distributed artworks

Dr Ele Carpenter, Goldsmiths University of London

Jon Thomson & Alison Craighead, UCL / Westminster

Andy Weir, Arts University Bournemouth

Slides available at: http://www.modern2020.eu/fileadmin/Final_Conference/Presentations/Day_2/...

Summary

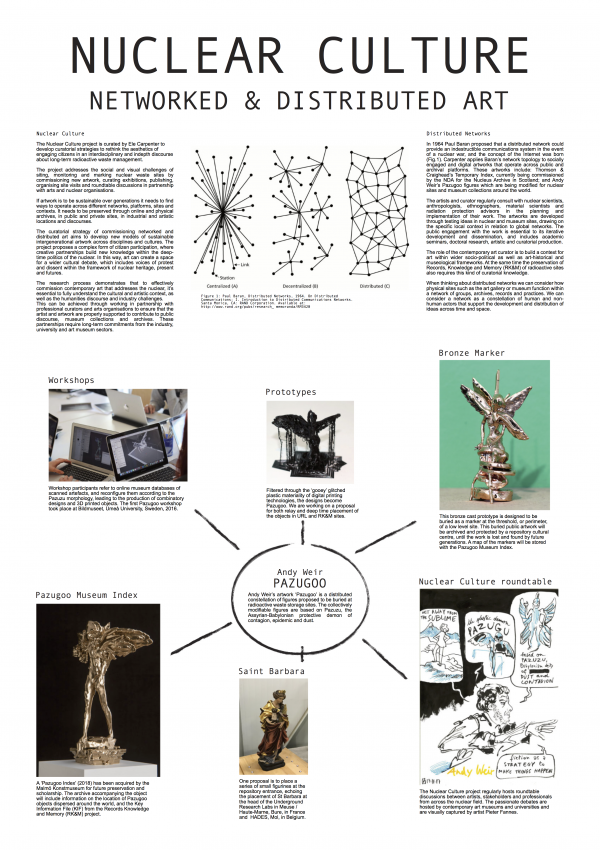

This paper introduces the Nuclear Culture project’s artistic and curatorial strategies for engaging citizens in an interdisciplinary and indepth discourse about long-term radioactive waste management through networked and distributed artworks.

There is an established humanities discourse on the relationship between social and technical challenges of long-term radioactive waste siting, monitoring and site marking, to which the visual arts can make a valuable contribution. Although there is a significant volume of contemporary visual art produced about this topic, there is a severe lack of curatorial work to establish its contribution to the wider arts, humanities and Radioactive Waste Management (RWM) discourse. The Nuclear Culture project aims to readdress this balance, enabling curatorial and artistic research to contribute new knowledge to the field of nuclear arts and humanities, and to be embedded in nuclear sites and museums around the world.

At the same time RWM is interested in the role that visual artists and their work can play in the public consultation and stakeholder engagement around geologic storage of high-level radioactive waste. Government directives encourage wide ranging forms of public engagement with the issues, hoping to establish public acceptance. However, the instrumentalisation of art for political ends will always be resisted by contemporary art. Instead the visual arts can provide a more complex and nuanced form of citizen participation, to establish social and technical networks for contemporary art where creative partnerships across sectors and disciplines build new knowledge within the deep time politics of the nuclear. In this way, art can create a space for a wider cultural debate, which includes voices of protest and dissent within the framework of nuclear heritage, present and futures.

In this poster curator Ele Carpenter and artists Andy Weir, Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead argue that the only way to commission contemporary art in response to the nuclear is to fully understand the cultural and artistic context, as well as the social and technical challenges of RWM. They argue that this can only be achieved through working in partnership with professional curators, arts organisations, galleries and museums to ensure that the work can productively contribute to public cultural discourse and archives. These partnerships require long-term strategic commitments from the industry, university and art museum sectors.

1. Introduction

The Nuclear Culture project, curated by Ele Carpenter, has successfully engaged over 100,000 people with artworks investigating radiological deep time and nuclear aesthetics by commissioning new artwork, curating exhibitions, organising site visits and roundtable discussions in partnership with arts organisations and nuclear agencies. The project has an ongoing impact on the contemporary debate about long-term storage of radioactive waste through publishing, reviews, book chapters, journal papers and touring films and artworks. The findings of the project are regularly presented at conferences on nuclear culture, nuclear history, nuclear humanities and European research programmes on art, archives, and site markers.[1]

Following the success of the ‘Perpetual Uncertainty’ exhibition[2] and The Nuclear Culture Source Book[3], Carpenter’s curatorial research in Nuclear Culture is now focusing on articulating a range of curatorial methodologies for commissioning artwork in nuclear contexts. Whilst there is a significant body of artwork being produced in response to deep time aesthetics, there is an important need for curatorial frameworks to enable artwork to contribute to the production of knowledge in the field through academic, social, public and artistic discourses and contexts. This abstract and poster focuses on the curatorial methodology of commissioning networked and distributed artworks through consultation with the Records, Knowledge & Memory (RK&M) project.[4]

The aim of commissioning artwork that has ‘distributed’ characteristics is to enable it to exist in many places at once, forming a network between sites, communities, digital and physical platforms. A distributed network was Paul Baran’s proposal for an indestructible communications system in the event of a nuclear war (Fig.1). Ele Carpenter applies the internet logic of Baran’s distributed network topology to socially engaged and new media artworks that can function on an international scale across public and archival platforms. These artworks include: Thomson & Craighead’s Temporary Index, currently being commissioned by the NDA for the Nucleus Archive at Wick, Scotland; and Andy Weir’s Pazugoo figures which are being modified for nuclear sites and museum collections around the world.

2. Methodology

The Nuclear Culture Research group employs a range of visual art and curatorial practice based research methods. These include situated field research, unstructured interviews, materials testing, and the iterative conceptual development of the relationship between theory and practice in the process of making. Collaborative methodologies for inter-disciplinary, multi-disciplinary and socially engaged practice are used to engage exhibition audiences, stakeholders and cross-sector agencies in indepth dialogue. Pedagogic workshops enable young people to participate in the creative development and production of the artwork. The public engagement with the work is an essential part of its iterative development and dissemination, and includes academic seminars, doctoral research, artistic production and curatorial production. Artworks are developed through testing the concept in nuclear and museum sites, drawing on the specific local context and issues. Artists and curators regularly consult with nuclear scientists, anthropologists, ethnographers, materials scientists and radiation protection advisors in the planning and implementation of their work.

The curatorial methodology to commission artwork that has ‘distributed’ characteristics enables it to exist in many places at once, forming a network between sites, communities and platforms. Influenced by Paul Baran’s network topologies for an indestructible communications system in the event of a nuclear war (Fig 1). Ele Carpenter considers the open source logic of Baran’s distributed network as a way of mapping socially engaged and new media artworks that operate across multiple digital, analogue and physical platforms.

Figure 1: Paul Baran, Distributed Networks, 1964. On Distributed Communications: I. Introduction to Distributed Communications Networks. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. Available at: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_ memoranda/RM3420

A centralized network (A) is based on an analogue communications structure such as radio, where one person can broadcast to many people, but the flow of communication is generally in one direction, from the center to the periphery. The decentralized network (B) starts to map our social networks, where community groups are able to communicate through smaller hubs. However note that they all connect to a central hub or node. The distributed network (C) uses the same network of stations or nodes, but provides links between as many of the nodes as possible. The survival strategy relies on information being able to communicated through multiple routes, like the internet packet switching capacity. When thinking about distributed networks we can consider how physical sites such as the art gallery or museum function within a network of groups, archives, records and practices. We might consider a network as a constellation of human and non-human actors that support the development and distribution of ideas across time and space.

If artwork is to be sustainable over generations it needs to operate across different networks, platforms, sites and contexts. It needs to be preserved through online and physical archives, in public and private sites, in industrial and artistic locations and discourses. The role of the curator of contemporary art is to build a context for art within wider socio-political as well as art-historical or museological frameworks. At the same time the preservation of Records, Knowledge and Memory of radioactive waste sites also requires this kind of curatorial knowledge to support its work.

3. Results

Two distributed and networked artworks developed through the Nuclear Culture project include Thomson & Craighead’s temporary index, currently being commissioned by the NDA for the Nucleus Archive at Wick, Scotland; and Andy Weir’s Pazugoo figures which are being modified for nuclear sites and museum collections around the world.

3.1. Andy Weir

Andy Weir is an artist investigating knowledge and agency within deep timescales through strategies of complicity and fiction. His artwork Pazugoo is a distributed constellation of figures proposed to be buried at specific sites of nuclear waste storage.

The collectively modifiable figures are based on Pazuzu, the Assyrian-Babylonian protective demon of contagion, epidemic and dust. Filtered through the ‘gooey’ glitched plastic materiality of current digital design and printing technologies, they become Pazugoo.

Religious and secular belief systems are a significant part of the debate about nuclear semiotics and how to communicate important knowledge into the deep future.[5] Weir’s project creates a thread of digital mutation through replicating the figure of Pazuzu who warns against dangers as intangible as dust and viruses, highlighting the invisibility and mutating force of radiation through a physical modification of the 3D model.

Figures 2 and 3: Andy Weir, Pazugoo, workshop designing and printing figures, Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Sweden, November 2016.

As part of the work, Andy Weir runs workshops to create and distribute Pazugoo figures (Figs 2. and 3.). Participants draw on online museum databases of scanned artefacts, and reconfigure them according to the Pazuzu morphology, leading to the production of combinatory designs and printed objects (Figs. 4 and 5).

We are now working on a proposal for both relay and deep time placement of the objects in URL sites. Andy Weir has made a series of small figurines in different materials which are planned to be placed at the entrance to every repository, echoing the placement of St Barbara at the head of Underground Research Laboratories in Meuse/Haute-Marne, Bure, in northern France and HADES, Mol, in Belgium.

Figure 4: Andy Weir, Pazugoo, design from workshop. Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Sweden, November 2016.

Figure 5: Andy Weir, Pazugoo Prototype S1N1 (2016), polylactic acid, 14cm x 9cm x 4cm.

Through the work, Weir proposes the importance of mythic fiction as a method for navigating between the immense timescales of nuclear storage and human cognition in the present. Pazugoo speculates on this through the fabulation of double-flight, a figure with an “excess of wings”,[6] it can be imagined flying billions of years into radiological deep time futures and back to the present.

This use of myth connects two temporal registers of the work: firstly, it draws attention to itself as a material object, slowly decaying over long timescales and becoming a future part of the earth in which it is buried; secondly it enters into discussions around waste now, opening critically engaged debates around responsibility, memory, fiction and materiality.

As a distributed work, it uses the museum exhibition as an ‘index’ to reference objects located and buried, collectively produced and dispersed around the world, connecting local, international and planetary scales of engagement. Following the ‘Perpetual Uncertainty’ exhibition, a Pazugoo Index (2018) has been acquired by the Malmö Konstmuseum collection for future preservation and scholarship. Examples of its distributed iterations include a clay burial ritual at a event marking time and toxicity in Amsterdam,[7] and its custodianship with local guides at the Maralinga site in Australia.[8]

3.2. Thomson & Craighead

Artists Jon Thomson & Alison Craighead investigate understanding of geological and planetary time through the relationship between live data and the material world. Their artwork temporary index is an array of decorative counters that mark sites of nuclear waste storage across the world. Each counter is a kind of totem marking the time in seconds that remains before these sites of entombed nuclear waste become safe again for humans. These timeframes range from as little as forty years or as much as one million years. A booklet accompanies the collection of counters, which describes each site in more detail, and providing contextual information about the human legacy of nuclear waste and what we as a species have done so far to deal with it.

Figure 6: Temporary index, Thomson & Craighead, 2016

At the core of the temporary index artwork is a database which drives an array of numeric counters which countdown the probabilistic decay of radioactive materials in seconds. The numbers at the bottom of each column count down in seconds. The counters can be presented as a full array or single totem, embedded in specific sites, syndicated online, presented in an art gallery, included in nuclear archives, and preserved in museum collections. These animated objects of contemplation are representations of time that far outstrip the human life cycle and provide us with a glimpse into the vast time scales that define the universe in which we live in, but which also represent a future limit of humanity’s temporal sphere of influence. The design of the counter demonstrates how human measurement of time is a process of linguistic and pictorial language.

Temporary index has been exhibited as a full array of counters at Carroll Fletcher Gallery, London (Fig 6), and the Malmö Konstmuseum in Sweden in 2018. In the Perpetual Uncertainty exhibition at Bildmuseet a single totem operates as a signpost, mapping the distance between the museum and the Chernobyl entombed reactor, tracing the downwind path of radiation that contaminated lichen in northern Sweden, and led to the culling of thousands of reindeer (Fig 7).

Figure 7: Thomson & Craighead, Temporary Index, Chernobyl Reactor #4, Ukraine. Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Sweden, 2016.

At Z33 House of Contemporary Art in Hasselt, 2017, the projected totem counted down the waste waiting to be entombed in the Low Level Waste site at Dessel, just a few miles from the art gallery. In 2019 the artists are creating a totem counter for the Nucleus archive at Wick, Scotland, commissioned by Highland Highlife and the Nuclear Decommissioning Agency (NDA).

We are now developing relationships with radioactive waste storage sites across Europe to build a series of live decay-rate counters, markers of time as well as place. Research for the project has included site visits to the LLW Ltd at Drigg, UK; Horonobe URL, Hokkaido, Japan; Nucleus Archive, Wick, Scotland, and HADES in Mol, Belgium.

4. Discussion

The Nuclear Culture project and the Pazugoo and temporary index artworks raise many important considerations for future partnerships between the visual arts and RK&M projects as they shift towards the public domain of archives and collections, and informal creative cultural practices.

The visual arts can introduce new conceptual and organisational frameworks for rethinking long-term communication challenges. Artists work between institutional and informal cultural practices that value culture on its own terms, address the limits of institutions. The visual arts can address over-arching and holistic concerns within the nuclear economy, and are not specific to one area of scientific specialism. The tendency for over-reliance on patriarchal closed knowledge management, needs to be addressed to develop distributed more resilient knowledge networks for RK&M. The RWM sector already faces problems with passing on knowledge as people retire, new cultural forms are needed that engage younger generations in nuclear culture.

Visual art addresses the RK&M “dual track” approach to future transmission as each generation of artists builds on the knowledge and practices of their predecessors. Artworks are the focus of gallery and museum education programmes to engage children and young people with complex ideas. The relay of intergenerational culture is also the focus of many socially engaged art practices. Whilst future communications are found in art objects preserved within collections, and public art commissioning processes.

Art can create informal spaces for dialogue that is reflexive, poetic, political and discursive without having to solve problems or comply with specific agendas. Alongside exhibitions, the Nuclear Culture project always organizes an interdisciplinary roundtable discussions to bring citizen stakeholders into discussion with artists, philosophers, architects, sociologists, anthropologists as well as scientists and engineers working in the nuclear field. The roundtable involves presentations from stakeholders, artists and scientists, followed by roundtable discussions in small groups so that everyone has a chance to share their knowledge and experience. In addition to the artists field research, exchange visits enable people to learn about new perspectives on radiation and the nuclear, often moving outside their comfort zone. For example Z33 in Hasselt organised regular tours of the Perpetual Uncertainty exhibition for residents of Mol and Dessel. Whilst in Malmo, museum staff were taken on a tour of their local nuclear power plant.

Museums also function as memory institutions, preserving contemporary objects in perpetuity for scholarship and public display. This includes visual arts objects, research based artworks and documentation of social processes. To achieve this artworks have to be recognised as having a cultural significance within the time in which they are made, so that they continue to reflect their contemporaneity. However, it should be noted that art museum collections tend not to include unrealised public art and architectural proposals. Markers of sites can aim to be permanent or temporary. Temporary public works may have a huge cultural impact which can be recorded and archived, whilst permanent works can be ignored or buried. So the only way to understand visual art as future cultural heritage is to work with its curators.

International mechanisms for contemporary nuclear artworks are both formal and informal. Artists such as Thomson and Craighead are interested in shared server protocols, and distributed artworks which can exist in many different forms as markers of time as well as site. Andy Weir’s Pazugoo figure as a spiritual marker of radioactive waste to be located at the entrance to URL’s and waste sites, buried in waste containers and placed in art galleries and museum collections. These ‘networked’ projects provide an opportunity to include the RK&M Key Information File (KIF) in their archival documentation, connecting museum collections with specific burial sites.

5. Conclusion

The visual arts can only offer methodologies for creative organisation, connecting institutional and public culture through a mix of closed and open source networks, strategic and tactical modes of operation, combining long-term vision with short term relevance.

Working with other disciplines can help to broadened the horizons of the context in which we work, giving people permission to think differently, and speak about concerns that the normative culture of their field doesn’t allow space for. It can help to articulate things people already know but don’t have the language or support to describe. The arts and humanities can think holistically, they don’t need to compartmentalize research-processes and knowledge in the same way as science and engineering. At the same time these disciplines are not homogenous, there are many arts and many sciences. But industry/ research or art/science partnerships often have expectations that art might articulate what is already visible and known, whilst artists might interrogate the interplay of visibility and invisibility both materially and politically in unexpected ways.

Care needs to be given to the methodologies of creative production and distribution. The RWM industry is commissioning artists proposals, but how is that work impacting on the visual arts? How is the work being critiqued, referenced, archived within visual culture?

Several centuries of curatorial work is needed for the nuclear archives to move into the public domain, and to be able to include art and politics. The first step is to establish a curatorial context for the commissioning, production and dissemination of these contemporary artworks within multiple discourses, to find new ways of embedding the complexity of radioactive waste management in our past, present and future cultures.

5. Acknowledgements

Dr Ele Carpenter is Curator of the Nuclear Culture project, and Director of the Nuclear Culture Research Group at Goldsmiths University of London where she is a Reader in Curating. She is a Visiting Research Fellow, Institute of the Arts, University of Cumbria.

Andy Weir is an artist, Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at Arts University Bournemouth and PhD researcher at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Jon Thomson is an artist and Professor of Fine Art at the Slade, UCL, London; Alison Craighead is an artist and Reader in Contemporary Art and Visual Culture at the University of Westminster, Lecturer in Art at Goldsmiths University of London.

References

[1] Carpenter, E,. 2018. Nuclear Culture Impact Report. Available at: http://nuclear.artscatalyst.org/

[2] ‘Perpetual Uncertainty’ Malmö Konstmuseum, Sweden (24 Feb – 26 Aug 2018), Z33 House of Contemporary Art, Hasselt, Belgium (Sept - Dec 2017), Bildmuseet, Umeå University, Sweden (Oct 2016 - April 2017). Curated by Ele Carpenter.

[3] Carpenter, E,. 2016. The Nuclear Culture Source Book. Black Dog Publishing, London, UK

[4] Preservation of Records, Knowledge and Memory (RK&M) across Generations, NEA. Available at: https://www.oecd-nea.org/rwm/rkm/

[5] Sebeok, T,. (1984) Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia. Indiana University / Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation, OH, USA.

[6] Negarestani, R,. 2008. Cyclonopedia. Re-press. Melbourne. p.88.

[7] Project by Anna Volkmar and Jacob Warren,’(In)human Time: Artistic Responses to Radiotoxicity’, May 2018.

[8] Project by Jacob Warren. Maralinga, Australia, is the site of British nuclear tests between 1956 and 1963, and part of land currently proposed as low to intermediate level radioactive waste storage site.